We Need New Dreams Tonight: U2’s America As Surrender and Aspiration

June 21, 2017

“I can’t believe the news today—too true an opening line—especially today.” A good friend messaged me this as I was driving to the stadium in Tampa, Florida to attend my fifth U2 show, an occasional but recurring pilgrimage that began in 1987, on the third leg of the original Joshua Tree tour.

Three hours before Larry Mullen, Jr. would pound out the cadence to “Sunday Bloody Sunday” in an anticipatory rhythm to the song’s opening lament, I was once again confronted with the scarred American landscape.

Earlier that day, a foreboding warning came from a tweet by a religious studies professor: “I feel horrible about everything going on today. If you do too, probably best to tap outta Twitter for a while…”

A quick scroll delivered successive gut punches. A gunman with a military grade rifle had opened fire on a congressional baseball practice in Washington, DC. Another workplace shooting and suicide had taken place in San Francisco, CA. And of course, a divided citizenry found themselves again all too eager to blame one another for the chaos.

The “Sunday Bloody Sunday” lyrics once required empathy and imagination, placing ourselves in the position of a young man coming of age in an Irish landscape torn apart by domestic terrorism, ignited by a Molotov cocktail of nationalism, religious dogmatism, and the dehumanization of the other. Now, no extra imagination or global empathy are needed, as this situation is ours, otherwise known as the daily American news cycle.

A U2 concert wouldn’t be, couldn’t be an escape from the fractured American landscape, could it? It wasn’t. Instead, it was a night of lament, recognition, and corporate confession punctuated with a dare to hope audaciously. With U2, we creatively act out the faith and dreams we allege to own with our professions. For two hours in the Florida humidity, some 60,000 people were invited to healing and commissioning in a place that Bono, in the midst of “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” declared to be a “church not made by human hands”.

Throughout the night the band and its earnest frontman led us in a collective liturgy. Cynics could view this tour as an exercise in resting on one’s laurels, a nostalgic visit to the band’s watershed transformation from college radio favorite to worldwide phenomenon. But U2’s musical catalogue at this point functions like the canon of a classic text.

While all songs are rooted in particular experiences and specific temporal and social locales, the reiteration of these tunes are never strict, mimetic representations. They evoke the past, engage the present, and offer what we might call a refiguration of time and our hope for the future. They weave a narrative that is at the same time biblical, historical, situational, and aspirational. It is the story of an Irish rock band with a love for America, a life unafraid of confronting the beloved and calling her to a grander vision.

Playing The Joshua Tree in its entirety is sandwiched purposefully in between the earnest yearnings of the band in the early 80’s and with some post-Joshua Tree hymns of celebration and hope amidst ambiguity, brokenness, and longing. They delivered an ode of love to America, the America that in fitful starts and stops was, is, and—most importantly, if we heed the call—is still to come.

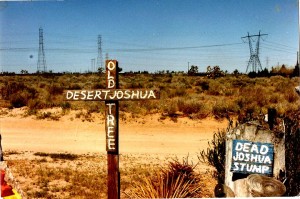

U2 historians are aware that The Joshua Tree album was at one time going to be called The Two Americas. It is a love song to America that contains the wonder and promise of a new love along with the pain and disappointment in relationships marked by broken promises. Throughout the night, Bono pursued us, cajoled us, encouraged and challenged us to reach for our best selves; selves we envision but have yet to embody with the consistency our self-promotion would seem to indicate. He called us to remember that, when ‘history and hope don’t rhyme,” it is an occasion for renewed action and not cynical resignation.

America today feels torn apart, irreparably fissured. The music pleaded with us to read the present with a lens of eschatological hope. Tonight, we can be as one. Up and down the catwalk and in front of the massive video display, Bono—ever the Irish salesman, rockstar, evangelist—serves as our proxy: loving America fiercely at a moment when most of us find ourselves either unable or unwilling to. This love is indiscriminate, holy, practical, and not impaired by rose-tinted sunglasses.

As the gathered crowd’s choral singalong with “Pride” began to fade and the enormous Joshua Tree screen illuminated in a red sea of lights, Bono invoked our communal liturgy in whispered tones. He reminded those gathered of our professed values: unity, compassion, justice, and tolerance. He also invoked the memories of those gunned down a year prior in Orlando’s Pulse nightclub, a vicious assault on a community yearning to breathe free, if just for a moment. That jarring memory juxtaposed with the memory of the King assassination laid bare to us the deep ambiguous scars marking the American spiritual landscape. As the Edge nimbly picked out the iconic opening chords of “Where the Streets Have No Name,” the frontman urged us gently to surrender, just as he had done with “Bad” a few moments earlier.

For The Joshua Tree part of the show, the band and the images on the behemoth screen engaged in a shamanistic ritual dance engaging the spirits of America—both benevolent and malevolent—calling us gathered to surrender in an honest, confessional and aspirational manner, holding open the possibility of healing.

I have to admit that often my U2 fandom resembles the posture of an insufferable door-to-door evangelist whose immersion in the message betrays a lack of critical distance between the material and my experience of it. And yet, in the backdrop of a nation buffeted by deep and seemingly intractable division, I heard “One” for the first time in the depth of the ineluctable brokenness which accompanies all human relationships where we—often in spite of our best intentions—hurt each other again and again. Maybe it is easier having someone to blame.

Yet in the depths of all these conflicted feelings, I found my attention periodically shifting from the light and sound spectacle on the stage to the illuminated American flag flying aloft from the upper deck of the stadium. In between the two images, there we were. All 60,000 of us formed into a temporary community, set apart for a moment as citizens of “U2opia,” before being sent back to an America gripped by fear and hate. Feeling deeply this tragic history that continues to manifest itself in our unfolding destiny, I was yet open to sacramental grace pushing through. We get to carry each other even though we’re not the same. What has been misunderstood as a rote retooling of the band’s past greatness is instead a call to a new narrative imagination and loving action.

Could a loving, open surrender to our landscape in both its aspirational glory and its violent transgressions address our longing for new dreams this night? For an America acquiesced to cynicism, the audacity of these guests called U2 can seem maudlin and naïve. But, if I can set aside the false certainties of cynical resignation and uncritical nationalism, if I can admit that, yes, we’re still running, then perhaps, such a message can “set me alight and [we will] punch a hole” through our dark night.

Maybe we will lay down our arms and see one another with love and compassion. Surrender. Carry each other. Again. And again. -Rick Quinn, @apophatic1

Florida show photos by Jaime Rodriguez, @jrodconcerts; American flag photo from U2.com social media stream TRALALA14

The Poet Tree: while you wait to rock out, don’t forget to read the screen!

May 22, 2017

In his review of the Joshua Tree revival for the New York Times, music critic Jon Pareles notes Bono’s lyrical debts to “language that drew on the Bible and Beat poetry.” This connection between sacred canon and subversive counterculture is an important one, and the summer rock recital of the 80s classic also invigorates the band’s respect for American writing, poetry in particular. As a matter of fact, fans waiting for the show will be treated to a digital anthology of poems, curated by U2.

When we got to our seats at Levi’s Stadium last Wednesday, we were early. With more than an hour before the show, this anticipation could have easily produced boredom or frustration. But we were not bored, not this night. As the sun started to set over the hills, we turned our attention to the mammoth stage that filled the south endzone.

The gold-hued backdrop would later double as an IMAX-style movie screen for the films that would accompany the concert, but for now on the right-hand side of the screen, the texts of poems, chosen by the band, scrolled before us. My sweet wife and I spent our time reading the poems out loud to each other. Each was incredibly powerful, and even though I am a huge poetry reader and poet myself, many were new to me.

Although U2 is an Irish band, these were all American poems by American poets, as American writers inspired the legendary 1987 album that they are touring behind to celebrate its 30th anniversary, playing all eleven tracks of the record in sequence for the first time in a live setting.

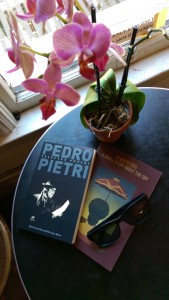

We heard from contemporary writers like Naomi Shihab Nye, Alberto Rios, or Elizabeth Alexander. We got challenged to our core by the late Nuyorican poet Pedro Pietri. We heard from classic writers like Carl Sandburg or the legendary Walt Whitman. Whitman warmed us with his words from Leaves of Grass. Words like “argue not concerning God” or “give alms to every one that asks” or “dismiss whatever insults your own soul” because according to good old Walt, these ideals will turn our entire lives into a poem.

What a great sentiment for the living fandom of the thousands not just watching, but participating in, this historic tour. Let’s make our entire lives a poem, or maybe a U2 song, or perhaps a psalm, a beatitude, or a Bible verse.

These particular phrases from Whitman remind me of the Kentucky farmer, poet, and believer Wendell Berry when he declares, “Love the Lord. Love the world. Love someone who does not deserve it.” Or “be joyful though you have considered all the facts.” I hope that perhaps U2 will add that Appalachian poem to their spontaneous anthology when they play shows in Tennessee and Kentucky next month.

A hardcore fan and fellow U2 scholar suggested that about 1% of the masses would read the poems, busy as they were, we suppose, with beers and merch lines, with Mixlr and Twitter. I hope that his estimate is low, but it might be high! But even if a mere one hundred of the thousands got excited about the poems and their messages, that is a great thing.

It didn’t matter to me about the other fans, because under the spell of these poems, I was enthralled. The very next day, I was hunting for poems on websites like poets.org or poetryfoundation.org or poemhunter.com before heading out on a pilgrimage to North Beach to the Beat mecca City Lights to collect some works by some of the poets I learned about and add to my always growing book collection.

Over at the Beat Museum, we found fellow U2 fan travelers, including Beth Nabi (@bethandbono), enjoying the city of San Francisco, before heading south for the Pasadena. shows. For at least some of us, books and poets and converging countecultures go hand-in-hand with rock fandoms. I’m excited to see if and how the digital anthology evolves or changes at the coming shows.

Check out some samples of the poetry shared on #U2TheJoshuaTree2017

William Matthews, “Why We Are Truly a Nation” from Selected Poems and Translations, 1969-1991

Because we rage inside

the old boundaries,

like a young girl leaving the Church,

scared of her parents.

Because we all dream of saving

the shaggy, dung-caked buffalo,

shielding the herd with our bodies.

Because grief unites us,

like the locked antlers of moose

who die on their knees in pairs.

William Matthews’s poetry has earned him a reputation as a master of well-turned phrases, wise sayings, and rich metaphors. Much of Matthews’s poetry explores the themes of life cycles, the passage of time, and the nature of human consciousness. In another type of poem, he focuses on his particular enthusiasms: jazz music, basketball, and his children.

Pedro Pietri, “Puerto Rican Obituary” from Selected Poetry

All died yesterday today

and will die again tomorrow

passing their bill collectors

on to the next of kin

All died

waiting for the garden of eden

to open up again

under a new management

All died

dreaming about america

waking them up in the middle of the night

screaming: Mira Mira

your name is on the winning lottery ticket

for one hundred thousand dollars

All died

hating the grocery stores

that sold them make-believe steak

and bullet-proof rice and beans

All died waiting dreaming and hating

Nuyorican poet and playwright Pedro Pietri was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, and raised in Manhattan. A few years after graduating from high school, he was drafted into the Army and served in the Vietnam War. Upon his return to New York, Pietri joined the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican Civil rights activist group. In the early 1970s, he co-founded the Nuyorican Poets Café with Miguel Piñero, Miguel Algarín, and others.

Carl Sandburg “Prairie” from Cornhuskers

I am here when the cities are gone.

I am here before the cities come.

I nourished the lonely men on horses.

I will keep the laughing men who ride iron.

I am dust of men.

Carl Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, writer, and editor who won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg was widely regarded as “a major figure in contemporary literature”, especially for volumes of his collected verse, including Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920). He enjoyed “unrivaled appeal as a poet in his day, perhaps because the breadth of his experiences connected him with so many strands of American life,” and at his death in 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson observed that “Carl Sandburg was more than the voice of America, more than the poet of its strength and genius. He was America.”

Alberto Rios, “The Border: A Double Sonnet” from A Small Story about the Sky

“The border is a moat but without a castle on either side.”

Born in 1952, Alberto Ríos the inaugural state poet laureate of Arizona and the author of many poetry collections, including A Small Story about the Sky (Copper Canyon Press, 2015). In 1981, he received the Walt Whitman Award for his collection Whispering to Fool the Wind (Sheep Meadow Press, 1982). He currently serves as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

Sherman Alexie, “The Powwow at the End of the World” from The Summer of Black Widows

I am told by many of you that I must forgive and so I shall after

that salmon leaps into the night air above the water, throws

a lightning bolt at the brush near my feet, and starts the fire

which will lead all of the lost Indians home. I am told

by many of you that I must forgive and so I shall

after we Indians have gathered around the fire with that salmon

who has three stories it must tell before sunrise: one story will teach us

how to pray; another story will make us laugh for hours;

the third story will give us reason to dance. I am told by many

of you that I must forgive and so I shall when I am dancing

with my tribe during the powwow at the end of the world.

Sherman Alexie, a Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Indian, was born on October 7, 1966, on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Wellpinit, Washington. He received his BA in American studies from Washington State University in Pullman. His books of poetry include Face (Hanging Loose, 2009), One Stick Song (2000), The Man Who Loves Salmon (1998), The Summer of Black Widows (1996), Water Flowing Home (1995), Old Shirts & New Skins (1993), First Indian on the Moon (1993), I Would Steal Horses (1992), and The Business of Fancydancing (1992).

Shirley Geok-lin Lim, “Learning to love America” from What the Fortune Teller Didn’t Say

because I walk barefoot in my house

because I have nursed my son at my breast

because he is a strong American boy

because I have seen his eyes redden when he is asked who he is

because he answers I don’t know

because to have a son is to have a country

because my son will bury me here

because countries are in our blood and we bleed them

because it is late and too late to change my mind

because it is time.

Born in Malacca, Malaysia, Shirley Geok-Lin Lim was raised by her Chinese father and attended missionary schools. Although her first languages were Malay and the Hokkin dialect of Chinese, she was able to read English by the time she was six. Lim emigrated to the United States after college, settling eventually in California. Her several books of poetry include Monsoon History: Selected Poems and What the Fortune Teller Didn’t Say.

Naomi Shihab Nye, “Kindness” from Words Under the Words: Selected Poems

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

Naomi Shihab Nye gives voice to her experience as an Arab-American through poems about heritage and peace that overflow with a humanitarian spirit.

Robinson Jeffers, “Juan Higera Creek” from Californians

There have I stopped, and though the unclouded sun

Flew high in loftiest heaven, no dapple of light

Flecked the large trunks below the leaves intense,

Nor flickered on your creek: murmuring it sought

The River of the South, which oceanward

Would sweep it down. I drank sweet water there,

And blessed your immortality. Not bronze,

Higera, nor yet marble cool the thirst;

Let bronze and marble of the rich and proud

Secure the names; your monument will last

Longer, of living water forest-pure.

Elizabeth Alexander, “Preliminary Sketches: Philadelphia” from The Venus Hottentot.

Which way to walk down these tree streets

and find home cooking, boundless love?

Double-dutching on front porches,

men in sleeveless undershirts.

I’m listening for the Philly sound—

Brother brother brotherly love.

Elizabeth Alexander’s career as a poet has been impressive. Her book American Sublime (2005) was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize, and in 2005 she was awarded the Jackson Poetry Prize. She is often recognized as a pivotal figure in African American poetry. When Barack Obama asked her to compose and read a poem for his Presidential inauguration, she joined the ranks of Robert Frost, Maya Angelou and Miller Williams; her poem, “Praise Song for the Day,” became a bestseller after it was published as a chapbook by Graywolf Press. Alexander writes on a variety of subjects, most notably race and gender, politics and history, and motherhood.

Celebration Road: Restless Reflections of Redemptive U2 Fandom, then & now

May 7, 2017

The Joshua Tree must be more than an album. And pondering its impact on me for its 30th birthday, this is more than just another mid-life crisis and exercise in nostalgia. 1987 was such a whirlwind year. 1986 and 1988, too. I graduated high school, started college, dropped out of college. I was finding myself and losing myself.

My first wave (1983-1988) of seriously following U2 would peak when I caught numerous shows that spring season, trekking around on the first leg of the North American tour, from Tempe to Los Angeles, from San Francisco and Detroit. My friendship with Maria McKee and Lone Justice, who would be tapped to open the shows on this tour, helped make this possible for a college student on a budget, as her generosity provided me guestlist tickets to the shows I attended.

The Lenten season had just begun when the album was first released, so the record’s desert Biblical tones seemed more than a perfect fit for the journey we were on. That March, I scrambled to throw together my dream of following the band’s world tour. If people could follow Springsteen or the Dead, then U2 needed that kind of traveling fanbase, too.

At the time, I was living in intentional Christian community in Atlanta, and the idea of running off to catch these shows seemed frivolous, even a decadent privilege, but I was possessed in my gut with that kind of fandom obsession only conjured by rock n roll bands. Within walking distance of where I lived, I could purchase the new tape for less than ten dollars, and I learned all the songs by listening to it on my cassette Walkman with headphones.

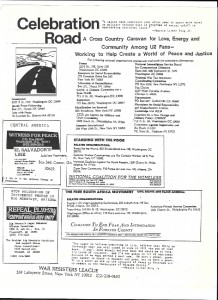

The social frame surrounding The Joshua Tree was for me more-than-intense, a fierce urban and rural religious resistance to Reagan-era America. We could feel it from the breathing bricks and overgrown weeds of our lives, manifest in mixtapes of classic rock. I was running from rally to protest, against the KKK or against intervention in Central America or against apartheid in South Africa or against the nuclear arms race. We had a lot to be against. Because of all this passion, I decided my touring with U2 needed a “mission statement,” so I conjured up “Celebration Road” as the nickname for my endeavor. I would pass out fliers at the shows, encouraging fans to get involved in movements for change.

Like the social and political edges, the musical ambiance that influenced The Joshua Tree also influenced me in heady and heavy ways. Like Bono and the gang in their late 20s, during my last days as a teenager, I rediscoverd the deeper cuts in the music of the late 1960s, music that had been on the turntables at my house my whole life. And after being mostly straightedge in high school, I was suddenly discovering the substances that made the 60s sound better. Like Bono has said about himself in the intervening years, I was as much punk as hippy. But so much both, that at times, I had been called hippypunk. For my sensibilities, U2 and R.E.M. of the late 1980s were much more avant-garde in musical and political spirit than their sudden “college rock” surge in popularity might suggest.

As much as I loved learning more Dylan or more Doors, more Beatles or more Hendrix, I could easily fall into rapturous moments with the Minutemen or the Meat Puppets or even hardcore like M.D.C. or Dead Kennedys.

Looking back, this time would be the last season of my youth when I would identify as a follower of Christ, before a two-decade descent into a crazed wilderness of addiction. My belief in Jesus had shaped, inspired, and guided me for so long, that it was hard to imagine life outside church and fellowship communities. My faith filled me with passion, and it shaped the entirety of my life, fueling my commitment to social justice. But the allure of the secular counterculture called loudly. I found myself dancing in the streets, debating in classrooms, and drinking at parties, seeking and craving and experiencing a version of the revolution that wasn’t rooted in a religious context.

Listening then and listening today, The Joshua Tree reaches the status of canon and brings a riveting liturgical experience. This is rock as revelation. The tracklisting is an order-of-service. Strangely, my experience of immersion on the opening leg of the tour would almost completely sate me. These concerts were undoubtedly church, but I would get somehow and somewhere disillusioned by the end of the line, and I was ready for extended visits to other rock-and-roll denominations. Months later, I would get spiritually restless, and some of the theological significance of the album for me would get lost, at least for awhile. Nevertheless, I have returned to this record at various times and places, and it has been rock scripture again and again, unpacking parts of my aching heart in new ways.

I stopped listening to U2 as much when I drifted away from Jesus. Then, when I made a decisive break with the church at 20 years old on Easter 1988, it was to listen to loud voices of hedonism, psychedelic and otherwise. When I returned to U2 in the 2000s, to this album along with all the others, especially All That You Can’t Leave Behind and How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, U2’s music helped draw me back to the source of my faith, the source of salvation, to Jesus.

U2 has always embodied for me what we today call the intersectional, the deeply connected. For them, the message is musical art as justice, brandishing a chorus or a guitar solo at that crossroads of God and spirituality, at the intersection of romantic love and movements for social change.

The music that a person connects with while growing up is the music that grabs heartstrings and holds you with gravity. To this music you can return, years and years later. My yearning for deep spirituality and romantic love and world peace were the swirling turbulence of the late 1980s, and this album brings those aches a profound amplification. Older versions of ourselves share the same concerns, and we will sing them out loud on this coming tour. -Andrew William Smith @teacheronradio

U2’s Prophetic Rage ‘N’ Roll: Rethinking “Sunday Bloody Sunday” Next To “Raised By Wolves”

June 1, 2015

If pushed to list the top 10 U2 songs from their expansive catalog, I would be hard pressed not to put “Sunday Bloody Sunday” at or near the top spot. The song converted me to the passionate crusade for justice that is a U2 trademark. It’s military drum cadence embodies what, in the evocative coinage of Joe Marvelli’s analysis, is an “aggressive pacifism.”

This song too cannot be divorced from the theater that is live rock n roll and Bono’s skills as a rock ‘n’ roll frontman. Their mastery of the performative in rock’s transcendent scope is why U2 is the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band to date. Their soaring belief in the power, as they sang, of “a red guitar, three chords, and the truth” allows them to harness this transcendent reach of rock ‘n’ roll in way that no other band does with the same consistency.

They are masters of the theatric and the performative and have spun their experiences into a body of work with an audacious reach beyond the limits of the present. No doubt, it sometimes misses in overreach. But when it connects one can be transported out of oneself to consider something bigger, grander, and “to come” in the biblical sense of an eschatological horizon akin to a “New Year’s Day.” But seeing this horizon is difficult in the midst of the raw matter of human life together. It is in this real context that U2 has been able to plumb rock’s depths of expressing anger, hope, and redemption. With its plaintive cries for a future beyond our destructive selves, “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is such a song.

In a 1987 World in Action documentary for Irish television, the Edge observed that “a lot of people think rock ‘n’ roll should be escapist, but why shouldn’t it face what is actually happening?” For a group of four young men coming of age in the midst of “The Troubles,” this question was both urgent and daunting. 1983′s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” was a bold answer. It teems with raw fury capturing the zeitgeist in which the post punk Irish quartet emerged. In the same documentary, Bono admits that, “We wrote ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ in a rage.” The rage is palpable in the pounding drum beat and the exasperated exhaustion of the opening line. And yet, it balances its analysis of the human condition (“trench is built within our heart”) with a horizon of hope (“tonight we can be as one”).

The song aural evocations are certainly strong but it is in the live performance that the song’s sound and fury are fully incarnated. For their often endless tinkering in the studio and the occasional brilliance that results, it is their adept handling of rock as performative theater in concert which signifies their greatness. “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is an illustrative case study. The iconic performance remains the one from the Under a Blood Red Sky concert film. Around the three minute mark near the end of the Edge’s guitar solo, a jackboot shod Bono emerges from the background with the white flag atop a huge pole, high-stepping to Larry Mullen, Jr.’s militaristic drumbeat. He forcefully plants the flag and entreats us to “let it fly,” leading the call to nonviolence by declaring “no more!”

The flag is a universal symbol of the cessation of hostilities and maybe a particular reference to the Irish Catholic priest, Edward Daly, who waved his white handkerchief aloft as others carried the unarmed wounded to safety in 1972′s horrific killing of 14 protestors in Derry, Ireland by an elite British paratroop regiment. U2′s use of the sonic and the visual connect concertgoers to a broken world. This version has a youthful exuberance that buoys the edginess of the song. There is a generational pushback that proclaims a prophetic NO to the cycle of violence. It embodies the headiness of youth spurred by dreams of changing the world.

But, as the lyrics lament, “how long must we sing this song?” As young people navigating our enlightenment with our restless energy, we can be tempted to think that our attention alone is enough to wrest history from the violent. Yet this song is a staple of the band’s canon and a fixture within their live shows. heir continuing relevance as four (now aging) lads bearing the self-professed mantle of “three chords and the truth” emerges as they successfully prevent the song from being a nostalgic greatest hits performance. Instead, the performance evolved with the band’s own expanded gaze. Birthed from “The Troubles,” it has come to speak to Beirut and Nicaragua, Soweto and Sarajevo, Baghdad and Tehran, and beyond.

In 2015′s Innocence and Experience tour, a stripped down “Sunday Bloody Sunday” has been paired with “Raised by Wolves,” displaying its ongoing, evocative weight. I am moved by the bare tone in this new haunting rendition. It is different than the militant exuberance of their 20-something selves. As a middle aged adult myself, it strikes me as the song of those who have lived long enough and seen too much to be naive about the human condition yet refuse to release their white knuckled grip on hope, vowing to “kick the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight.”

Juxtaposing it with the raw, new track “Raised by Wolves” serves as forceful reminder of the harsh context in which this hope must be spoken and lived with a vulnerable courage. It is a world in which the fervor of our beliefs can be twisted in on ourselves and spring outward in a bloody “purification” of those who oppose us.

It is a world in which the cry from the new song, “I don’t believe anymore…” is both an expression of exasperation at nihilism and a prophetic refusal of causes and crusades no matter how religiously infused. Thirty two years on from its first performances, this song is still “not a rebel song,” but is a call to all of us to face the human condition without blinking and with sober, relentless hope. It is not resignation to the inevitable but a call to action. As Bono invited in U2 Go Home: Live from Slane Castle, “…if you’re the praying kind, turn this song into a prayer.” It is lament. How long? It is petition. No More! It’s shrill and stilling focus on violence somehwere remains a prayer for an end to violence everywhere. Amen.

-Rick Quinn

Rainbows Over Dublin, U2′s Gay Pride in Arizona, & the Arc of Bono’s Activism

May 26, 2015

When Ireland became the first country to legalize same-gender marriage by popular mandate, double rainbows appeared over Dublin, and an Irish rock band transformed their Arizona concert into a gay-rights celebration. Almost 30 years ago, Bono endured threats from angry Arizonans for his support of the US national holiday for the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. But on Saturday, Bono invoked King as peacemaker as U2 celebrated the victory of love, turning the song “Pride (In The Name of Love)” into an anthem for gay pride.

U2 had begun expressing their strong support for #VoteYes on their website and social media outlets in the days leading up to the vote, even though they were on tour in North America. This victory for Ireland was a particularly poignant moment for Bono to be his most audacious activist from the arena stage on an issue local to Ireland–and not on the talking-points handout from the ONE campaign–as important as those issues remain. Bono’s speech on Saturday in Arizona during “Pride” profoundly united his faith, poltics, and belief in love in profound and eloquent ways.

Bono shared, “This is a moment to thank the people who bring us peace. It’s a moment for us to thank the people who brought peace to our country. We have peace in Ireland today! And in fact on this very day we have true equality in Ireland. Because millions turned up to vote yesterday to say, ‘love is the highest law in the land! Love! The biggest turnout in the history of the state, to say, ‘love is the highest law in the land!’ Because if God loves us, whoever we love, wherever we come from… then why can’t the state?’”

This victory for same-gender love being likened by Bono to God’s love provides us a powerful moment to reflect on the evolution of U2’s faith and activism. Back in the 1980s, after albums like War, The Unforgettable Fire, and The Joshua Tree, Bono and U2 epitomized the progressive activism of anti-war and anti-apartheid positions, particularly criticizing the Reagan administration’s interventionist intrusions in Central America with a track like “Bullet The Blue Sky.” Because the band’s activism expressed their faith in Jesus Christ, the lord, savior, and peaceful liberator, they took hits in the secular cynical rock press for being messianic crusaders. Come down from the cross, the critics chastised Bono, we could use the wood for kindling.

In the 1990s, Bono dealt with his Jesus-complex by dressing up in drag or like the devil. The trio of albums that chopped down the Joshua Tree mythos were Situationism on speed, the pop culture capitalist rock star Spectacle turned inside-out and turned up to eleven. This Bono was still liberal in a sense, but with a buzzed irony we couldn’t quite grasp. A lot of people didn’t get it. Of course the band maintained its activism during the Zoo years, speaking out against the resuregence of hate groups and about the wars in the former Yugoslavia.

By the 2000s, crusading Bono was back in full swing, and his bandmates went along, always faithfully yet sometimes begrudgingly, as he worked on issues related to ending global poverty with a new passion. Bono also injected his faith into the conversation more than ever before, turning his public speaking gigs into real opportunities to preach the gospel of good news for the poor, such as at the White House prayer breakfast or the NAACP awards. The singer’s ability to move a crowd with goose-bumps and the gravity that generates actions is not limited to his songs, as his speeches are just as stunning.

This new on-fire Bono brought unprecedented attention to the causes he championed and unfettered backlash from the political left. His own personal wealth that puts him at the tippy-top of the 1% and his band’s corporate and tax practices have resulted in a drumbeat of negativity towards the superstar and his bandmates. His strategies for ending poverty, no matter how effective or ineffective, have been judged for their association with neoliberalism. But that didn’t stop Bono from working nonstop on what he believed would benefit the most people.

In his many visits to the United States, Bono became committed to tapping the missional spirit among evangelical Christians with hopes they would be active in the movement to end poverty. These friendships have been well-documented and the partnerships with religious conservatives in the fight against poverty wildly successful. This has led to many powerful alliances with contemporary Christian musicians and ministers and many conservative US politicians. His friendships and collaborations with the likes of Billy Graham, Bill Frist, George Bush, and Rick Santorum were fodder for his critics on the left. Even as recently as 2013, he gave an interview with the arch-conservative organization Focus on the Family.

During the Vertigo tour, the War on Terror was on everyone’s minds. Bono repurposed the Nietzsche quote about not becoming a monster in order to defeat a monster and turned it into a prayer. He talked about Islam, Judaism, and Christianity being Abrahamic kin and wore his “COEXIST” blindfold as he dramatized torture during “Bullet The Blue Sky.” The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights was recorded and made a regular part of the show. But Bono stopped shy of any Code Pink-type tactics or even overt statements against the war in Iraq. He dedicated “Running To Stand Still” to the troops.

Is Bono progressive, conservative, moderate, or what? Does his faith make him some kind of evangelical free agent? So this much is clear: a person doesn’t necessarily become a religious conservative by hanging out with religious conservatives? Some things consistent about Bono are his passion and work-ethic, which are always in full-effect, at full-volume, for what he believes are the greatest goods, whether his fans or critics agree with all his political maneuvers or not.

Surely, education and cultural change on same-gender love have been so effective worldwide that more and more people, liberal and conservative, now support marriage equality. What Bono made clear in Arizona last Saturday, though, is that God is love and when love is the law, love can change laws.

On Songs of Innocence, the message of U2 comes full circle. With “Raised Like Wolves,” problems of violence and religious intolerance trouble the lyricist channeling his younger self. Back on albums like War with its white flag of hope and surrender, Bono was one of the first Christians I heard call himself “spiritual but not religious” because of the damage that religious dogma can do. In the new shows, “Bullet The Blue Sky” has been completely revised yet again, as the younger Bono lectures the older Bono and vice-versa. A barricade exists within the self between the agitator and the negotiator. Then, before the song ends, Bono adopts the “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” pose and is rapping about the racial strife in Ferguson. All these are good reminders to Bono and to us, as we look at the long arc of his career in activism and art.

In 2000, the late Coretta Scott King, widow of the slain civil rights leader to whom U2 dedicates two songs, said, “I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream to make room at the table of brotherhood and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people.” What is true in Ireland today is true in 37 states of the United States. The pending Supreme Court decision on cases brought by gay couples in states without marriage equality may come as soon as next month, when Gay Pride parades are celebrated throughout the US and while U2 are still on tour here.

–Andrew William Smith

Check out the video of Pride from Saturday, May 23: https://youtu.be/TuYr7dfyCn0

Photos: (in story) from U2′s Instagram leading up to the Ireland vote on gay marriage.

On the front page of Interference: Bono photo by Danny Lawson/PA Wire

Rainbow picture: @karltims on Twitter

Recent Comments