vivaSA

War Child

'People of the Book': An erudite 'Da Vinci Code'

People of the Book

By Geraldine Brooks

By Susan Kelly, USA TODAY

Geraldine Brooks' novel People of the Book arrives with high expectations. Booksellers are comparing it to The Da Vinci Code and calling it the first literary hit of 2008.

Does Brooks deliver? Yes, and with less flash and more substance than Da Vinci. People of the Book is not as cinematic as Dan Brown's 2003 religious thriller, but Brooks is a skilled storyteller who also casts a spell of intrigue and evil in which demons feign divinity.

But her careful research and the novel's historic underpinnings make it highly unlikely People will face the criticism of factual flaws that dogged Da Vinci.

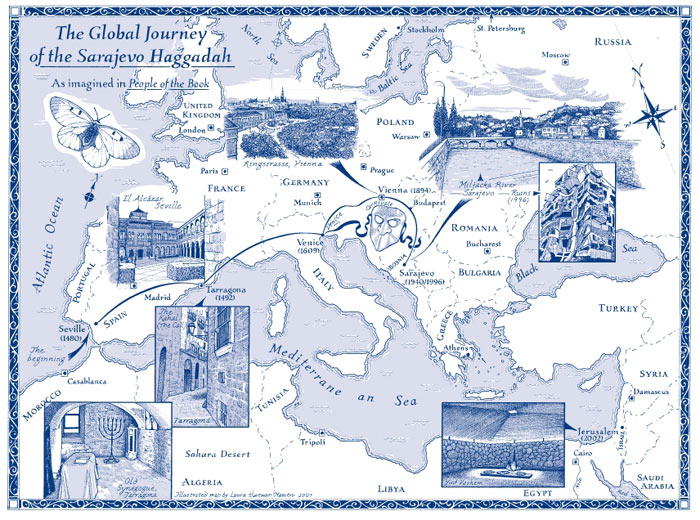

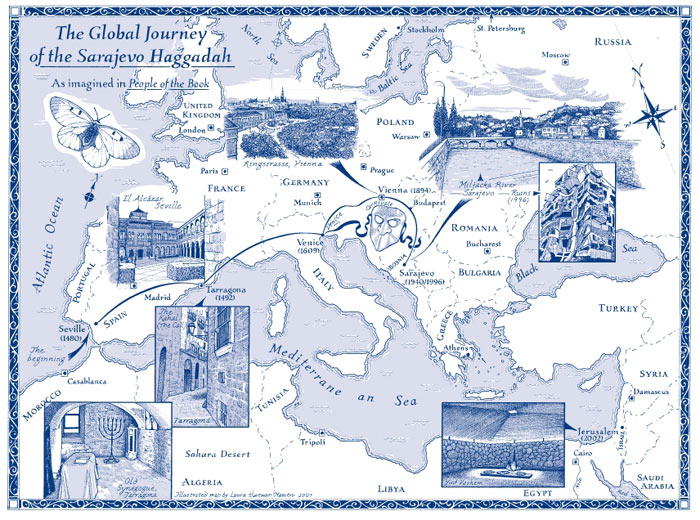

The titular book is a real one, the Sarajevo Haggadah. The richly illuminated Hebrew text, which recounts the story of Exodus, dates from medieval Spain. For more than 600 years, it was carried across borders and over seas to escape political and religious cataclysms.

The Haggadah came to rest in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, and Brooks, who covered the war in Bosnia for The Wall Street Journal, imagines its perilous journey in her third novel.

Brooks won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for March, a retelling of Little Women from the perspective of the father who goes off to war. Her first novel, Year of Wonders, about a 17th-century village shrouded by plague, was acclaimed for bringing new luster to historical fiction.

The author says that though People of the Book has its roots in history, much of it is her own invention. Her chief creation is Hanna Heath, an Australian book conservator hired to restore the Haggadah after it survives the shelling of Sarajevo.

As the sardonic Aussie tends the manuscript, she finds tiny artifacts — part of an insect's wing, a wine stain, salt crystals and a white hair. Believing they are keys to the book's mysterious past, Hanna takes samples to be analyzed.

Brooks alternates Hanna's account of her work and unraveling personal life with the story of those relics. The insect's wing takes us to Sarajevo at the dawn of World War II as the Nazis steal Jewish treasures.

The wine stain leads to Venice, 1609, where a tormented priest executes a papal order to burn most books written by Jews. The salt takes the story to 1492 and the Hebrew scribe who writes the text on the eve of the Jews' expulsion from Spain.

And finally, the hair harks back to Seville in 1480 and the unmasking of the artist. Hanna's own troubled past and uncertain future dovetail neatly with those of the book as both face betrayal from unexpected sources.

If Brooks becomes the new patron saint of booksellers, she deserves it. The stories of the Sarajevo Haggadah, both factual and fictional, are stirring testaments to the people of many faiths who risked all to save this priceless work.

http://www.usatoday.com/life/books/reviews/2008-01-09-peope-of-the-book_N.htm

People of the Book

By Geraldine Brooks

By Susan Kelly, USA TODAY

Geraldine Brooks' novel People of the Book arrives with high expectations. Booksellers are comparing it to The Da Vinci Code and calling it the first literary hit of 2008.

Does Brooks deliver? Yes, and with less flash and more substance than Da Vinci. People of the Book is not as cinematic as Dan Brown's 2003 religious thriller, but Brooks is a skilled storyteller who also casts a spell of intrigue and evil in which demons feign divinity.

But her careful research and the novel's historic underpinnings make it highly unlikely People will face the criticism of factual flaws that dogged Da Vinci.

The titular book is a real one, the Sarajevo Haggadah. The richly illuminated Hebrew text, which recounts the story of Exodus, dates from medieval Spain. For more than 600 years, it was carried across borders and over seas to escape political and religious cataclysms.

The Haggadah came to rest in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, and Brooks, who covered the war in Bosnia for The Wall Street Journal, imagines its perilous journey in her third novel.

Brooks won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for March, a retelling of Little Women from the perspective of the father who goes off to war. Her first novel, Year of Wonders, about a 17th-century village shrouded by plague, was acclaimed for bringing new luster to historical fiction.

The author says that though People of the Book has its roots in history, much of it is her own invention. Her chief creation is Hanna Heath, an Australian book conservator hired to restore the Haggadah after it survives the shelling of Sarajevo.

As the sardonic Aussie tends the manuscript, she finds tiny artifacts — part of an insect's wing, a wine stain, salt crystals and a white hair. Believing they are keys to the book's mysterious past, Hanna takes samples to be analyzed.

Brooks alternates Hanna's account of her work and unraveling personal life with the story of those relics. The insect's wing takes us to Sarajevo at the dawn of World War II as the Nazis steal Jewish treasures.

The wine stain leads to Venice, 1609, where a tormented priest executes a papal order to burn most books written by Jews. The salt takes the story to 1492 and the Hebrew scribe who writes the text on the eve of the Jews' expulsion from Spain.

And finally, the hair harks back to Seville in 1480 and the unmasking of the artist. Hanna's own troubled past and uncertain future dovetail neatly with those of the book as both face betrayal from unexpected sources.

If Brooks becomes the new patron saint of booksellers, she deserves it. The stories of the Sarajevo Haggadah, both factual and fictional, are stirring testaments to the people of many faiths who risked all to save this priceless work.

http://www.usatoday.com/life/books/reviews/2008-01-09-peope-of-the-book_N.htm