You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ali 3

- Thread starter Souly

- Start date

The friendliest place on the web for anyone that follows U2.

If you have answers, please help by responding to the unanswered posts.

If you have answers, please help by responding to the unanswered posts.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Niamh_Saoirse

Rock n' Roll Doggie FOB

well done, Kel!

lauramullen

Blue Crack Distributor

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2002

- Messages

- 52,111

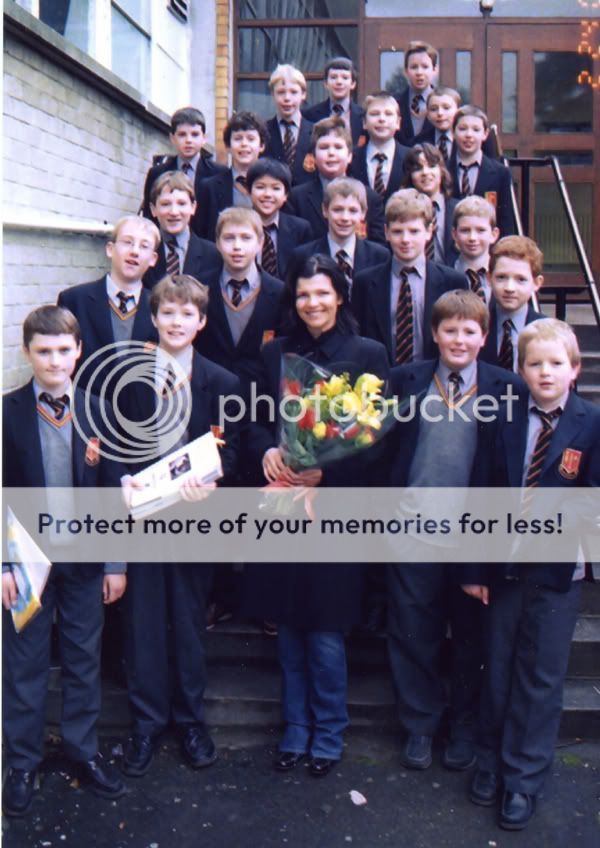

The look on that boy's face is priceless. The one that Ali has her arm around. He looks like he is on cloud nine.

Niamh_Saoirse

Rock n' Roll Doggie FOB

Within this article, you can find a pic of Ali and her family in Sydney.

http://www.heraldsun.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5478,18403946%5E663,00.html

http://www.heraldsun.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5478,18403946%5E663,00.html

Niamh_Saoirse

Rock n' Roll Doggie FOB

Galeongirl

Galeonbroad

aww the boys look cute!

thanks for posting the article..

Bono really seems to be glued in his denim jacket.. haven't seen pics of himn without it for a while....

Bono really seems to be glued in his denim jacket.. haven't seen pics of himn without it for a while....

ADAM!!!!!!!! ><

thanks for posting the article..

Bono really seems to be glued in his denim jacket.. haven't seen pics of himn without it for a while....

Bono really seems to be glued in his denim jacket.. haven't seen pics of himn without it for a while....

ADAM!!!!!!!! ><

u2trinity

Rock n' Roll Doggie VIP PASS

kellyahern said:

I changed the url to 05 and got this

Ali , is The Princess Of Ireland .

lauramullen

Blue Crack Distributor

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2002

- Messages

- 52,111

The boys look so cute with Ali. Thanks for posting.

Niamh_Saoirse

Rock n' Roll Doggie FOB

Interview with Adi Roche. Ali is mentioned a few times in it. Adi is such an amazing woman.

A mother to many millions

ADI ROCHE: 'My greatest failing - which is also the flip side, giving strength to everything - is that I'm a workaholic. I will work to the detriment of everything else - to the detriment of life really.' Photo: Gerry Mooney

'THERE is nothing in the world like the devotion of a married woman," Oscar Wilde once said. "It is a thing no married man knows anything about."

Perhaps not even Sean Roche . . . His wife has been beatified, variously, as the European Woman Laureate, Irish Person of the Year, and European Person of the Year, for her work as executive director and founder of the Chernobyl Children's Project. Her devotion to the poor souls of that part of the world has made Adi Roche one of the greatest living Irish women.

It can't, however, be easy being married to a saint . . .

"It was my husband's birthday yesterday and I wasn't there," Adi says. "That happens all the time. I'm usually not there for the birthday or the wedding anniversary."

Does he ever say to you: 'What about me?'

"Sometimes he does. And when he does it is really serious because he doesn't say it very often. He is a very, very tolerant human being. I don't know anybody or any man who would tolerate me."

Sean, a music teacher in CBC Cork, would, she says, have walked out a long time ago if he was anyone else. "And I really mean that, because I have . . . I won't say 'provoked' him . . . but not prioritised the relationship a lot of the time.

"But it is because he realises this is such a significant thing that he gives me the space to do it. It's not about getting the permission, because I'm a total free spirit," she says.

"Sean is great. He never says: 'It's a long time since you were at home for a Saturday, or to cook the Sunday dinner.' I'm the one who's out doing it - but he carries the burden. He financially supports me to do that, because I am a full-time volunteer. That's a huge gift. That's a lot of tolerance."

Adi's sister had very little tolerance for her when they were growing up in Clonmel, Co Tipperary. By her own admission, Adi was a pest who wanted to know where her big sister was going and why she couldn't go too. "I had a wonderful life in Clonmel, full of the usual things - chasing fellas, dancing, going to parties and singing songs," she remembers.

Adi's childhood dream was to be the next Margot Fonteyn. She even danced semi-professionally in Cork as a member of the Cork Ballet Company until she was 21.

Adi was six when she danced for the first time. "It was in a tutu. I used to love dressing up as a kid."

She hasn't lost that penchant for dressing up. When she attended the 2004 Academy Awards to pick up an Oscar for Chernobyl Heart, winner in the Best Short Documentary category, Roche looked ravishing in a red rig-out by her favourite Irish designer Mariad Whisker and a pair of problematic Manolo Blahniks she borrowed from a friend.

"I felt I had dropped in from another planet, because I am so not used to that world. Nori [her colleague] and I were the great unknowns. Nobody was interested in us. We were going down the famous red carpet and all the beautiful people were there and we decided that we had the only two faces in the whole of Hollywood that moved. Everybody was botoxed, lifted, ticked, stretched, pinned. We were the only two that looked real."

She recalls sitting outside the Vanity Fair party to rest her tootsies, tortured by the borrowed Manolos. To relieve the pain, she did a live interview for Gerry Ryan's RTE radio show. Her friend Ali Hewson, she says, "was listening to it in her car, and she said she had to pull over because she thought she'd have a crash she was laughing so much."

Adi seems very much the wide-eyed country girl from Clonmel when she talks of the excitement of staying in the hotel in which the movie Pretty Woman was made. But that is as far as her sense of wonderment at Hollywood went. "Because we weren't anybody we were able to be voyeurs. It's a world that they can definitely have. We went to all the after parties and saw all the stars, but it was a very lonely experience. There was an emptiness.

"I was sitting there thinking: 'We've won the Oscar but what does it mean?' At the end of the day it's a piece of metal. A grand piece of metal, but what does it mean to the people's lives who we invaded to make the film? What difference does it make to them? To me, it's always about that."

Adi is a product of both Cork and Tipperary. Her parents Sean and Chris were from Cork but lived in Clonmel. She clearly inherited her concept of social responsibility from them, as both were active in the St Vincent de Paul, Meals On Wheels - and Fianna Fail, though Adi herself, of course, ran unsuccessfully for the Presidency in 1997 with the backing of the Labour party.

She believes she also inherited her late father's work ethic. "My greatest failing - which is also the flip side, giving strength to everything - is that I'm a workaholic. I will work to the detriment of everything else - to the detriment of life, really. Actually, the recent death of my mother has given me an opportunity to rethink that. To slow down and say: 'Get a life.'"

And have you got a life?

"I'm actually starting to get a life. I'm actually singing with the girls. We're called The Bubbles," she says, referring to the collective of female singers specialising in a cappella and three-part harmonies. "I love a good time. If you saw me out on the town . . . "

So when was the last time she got physically ill from a night's drinking?

"God help us! That would be going back to another life."

ADI still finds the loss of her mother hard to bear. She lived with Adi and Sean for eight years. In fact, Adi was the primary carer for both her parents over almost a decade. (Her father, who died four years ago, had Alzheimer's.)

"Parting with my mother was very hard," she says. She was finishing the new Chernobyl Heart book when her mother went into a coma. "So the book has very mixed blessings for me. The last time I was with my brothers and my sister was at the funeral."

The day after the funeral Adi had to fly out to Ukraine with an RTE film crew. She couldn't cancel because it was something she had planned for six months. On that plane journey, Adi says she felt "a hole in my heart".

"I felt a whole mixture of emotions, but I also felt that my mother would have wanted me to go. She was one of my strongest advocates. She saw how lonely this job is as well. People just see the public persona."

And if there is a God, maybe he was testing you by showing you a fraction of the pain that the people in Chernobyl have gone through?

"Definitely. Through this work I have learned so much. It's so humbling. It is not about us being the benevolent ones or the great benefactors. The gift you get back you can't quantify, because it tells you about what it is to be a human, the privilege it is to be alive.

"There is something very cathartic as well. It's not about altruism for me. I say that to you in all honesty. It is as much about my own salvation as it is about doing good and I feel better for that."

It is not about Adi Roche sanctifying herself?

"Come here!" she laughs through the fog of a sudden deep culchie accent. "The broken wings, the broken halo, the fallen angel . . . absolutely, that is moi. Totally. And that's where I want to be. And there by the grace of God go all of us.

"The Belarussians are a kind people. If something happened in Sellafield, they'd have been the first to come to us. None of us can afford to be sanctimonious. None of us can afford to say: 'It's them and it's not us.'"

Adi is in the Merrion Hotel in Dublin to talk up Chernobyl Heart: 20 Years On, her new book that documents the physical, emotional and psychological pain that the nuclear disaster caused. (The book needs no talking up: with photos by former Sunday Independent photographer Julien Behal, it is equal parts harrowing and uplifting.)

She hopes that readers of the book will find it "breaks their hearts sometimes, but their hearts will soar with delight and pleasure when they read some stories." She also hopes the reader will cry the tears of those who have died, some of whose testimonials are told movingly here.

Adi wanted to give them a voice "regardless of whether they are still alive or not. They are environmental refugees, a status not recognised by the UN because no one ever anticipated an enviromental disaster such as this. They are a displaced people, hundreds and thousands of them.

"Sometimes they don't tell other people that they are Chernobyl survivors, because they are ashamed. Many of them have commited suicide, many have abandoned their own children - not because they don't love them, because they feel absolute despair and absolute paralysis."

Adi wanted to tell the human interest stories in the book because, she says, no statistics will ever "reflect the broken hearts and the pain and the agony. At the same time, we wanted to have a balance that wouldn't scare people off by having people so distraught that they can't read to the end."

She desperately wants readers to come to that beacon of hope at the end where they will hear about "thelikes of Ali and others who helped to make things happen, like the nurses, the doctors, the truckers."

Ali Hewson, a patron of Chernobyl Children's Project International, and Adi work well together. Ali is godchild to one of the Chernobyl children, Anna Gabriel. In 1993, Ali, according to Adi "agreed to break her own privacy" by going to Belarus to present Black Wind, White Land, a poignant documentary about life in post-disaster Chernobyl. Ever since, Ali and Adi have shared a devotion to revealing the truth of what they saw in Chernobyl.

"I think it touched a part very deep inside her. We were filming in a home for abandoned children and we ended up bringing home a child who was four or five months old at the time. She was about to be put in a mental asylum."

The child is now grown into a fine young woman and lives in West Cork. Ali, says Adi, is the consummate godmother, having attended all Anna's special occasions such as her confirmation, holy communion and birthdays.

As for Ali's immense contribution to the Chernobyl Children's Project, Adi says that people who are in the public eye "have a responsibility to use that celebrity for good".

"All I can say in relation to Ali is that - for me - she is the anchor person. She is far more reticent than I'd be. I am feet first. I want to save every single child, all four million. Ali would be of the philosophy that we do it one by one. That is far more realistic. In a sense, we have adopted that as our own mantra."

Is that why you work so well as a partnership, because you are such opposites?

"Ali says I talk a lot," says Adi. "When we drive in convoys, Ali does the driving and I do the talking. There is a serenity to Ali and her energy. Ali brings the reflective to things. When I want to dive feet-first into a situation, she wants to weigh up the pros and cons. Ali would be more pragmatic, more a strategist than I would be. There is a fine balance there."

Her mood turns darker as she talks about the nuclear radiation genie escaping out of the Chernobyl bottle. The cement tomb placed over the former power plant is far from effective. She talks with passion about the many workers who tunnelled under the reactor to install a cooling system "which saved Europe from being wiped out, because Chernobyl was about to have a second explosion."

Some 25,000 of the workers have died as a result and another 70,000 are dying at the moment. "I know many of these lads," she says. "I know one extraordinary helicopter pilot who was older than the others and had had his kids." He is now dying of strontium poisoning. "These guys sacrificed themselves."

In a way, so did Adi Roche. The Clonmel superwoman didn't die in Chernobyl, but she has practically given up her life for it. "I have," she agrees, "but I don't want that to sound self-sacrificing."

You don't have children, Adi. "I don't, because we had to make a decision in relation to the work. In a way, I would say that I have millions of kids. I honestly believe you don't have to have the umbilical cord connection to feel absolute, unconditional love for another human, whether it's a child, an infant or an adult."

"In the Seventies, we genuinely believed we were on the brink of nuclear annihilation. People really did wonder if they should have children or not. We made a decision based on what we knew and the ways things were going. But there are so many kids in the world that there's plenty of love to go around."

She adds that this means when when she visits orphanages or institutions, shecan completely give herself over to the children there. "Because I don't feel guilty that I've left kids at home. I would be up for neglect if I actually had kids. It would be one or the other."

She tells me that, once upon a time, the "conservative, strait-laced" Clonmel girl had a life that she thought would be about boy-meets-girl, gets engaged, married, has kids - the whole package.

She did meet the man, but what stopped that union flowering into the classic nuclear family (so to speak) was that Adi became involved in the anti-Nuclear Movement.

Her brother Donal was living in the US at the time, and his wife was having a baby. Adi arranged to fly over for the birth of the child as she was asked to be godmother.

The night before she flew out, there was newsflash on RTE about a nuclear accident on Three Mile Island in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania - near where Adi's brother lived.

Adi can recall turning to Sean at the time and asking him two questions. 'What's radiation?' and 'What's a nuclear reactor?' Sean said he didn't know, "but they want to build one of those down in Wexford" - a reference to Carnsore Point in Co Wexford.

"That was the beginning of it for me. I never had a life plan," she says, as she finishes her tea. "Because if I had known all those years ago that this was what I was going to end up doing, I'd have run in the opposite direction."

Thank God for the people of Chernobyl that she didn't.

'Chernobyl Heart: 20 Years On' by Adi Roche is published by New Island, €19.99

Barry Egan

A mother to many millions

ADI ROCHE: 'My greatest failing - which is also the flip side, giving strength to everything - is that I'm a workaholic. I will work to the detriment of everything else - to the detriment of life really.' Photo: Gerry Mooney

'THERE is nothing in the world like the devotion of a married woman," Oscar Wilde once said. "It is a thing no married man knows anything about."

Perhaps not even Sean Roche . . . His wife has been beatified, variously, as the European Woman Laureate, Irish Person of the Year, and European Person of the Year, for her work as executive director and founder of the Chernobyl Children's Project. Her devotion to the poor souls of that part of the world has made Adi Roche one of the greatest living Irish women.

It can't, however, be easy being married to a saint . . .

"It was my husband's birthday yesterday and I wasn't there," Adi says. "That happens all the time. I'm usually not there for the birthday or the wedding anniversary."

Does he ever say to you: 'What about me?'

"Sometimes he does. And when he does it is really serious because he doesn't say it very often. He is a very, very tolerant human being. I don't know anybody or any man who would tolerate me."

Sean, a music teacher in CBC Cork, would, she says, have walked out a long time ago if he was anyone else. "And I really mean that, because I have . . . I won't say 'provoked' him . . . but not prioritised the relationship a lot of the time.

"But it is because he realises this is such a significant thing that he gives me the space to do it. It's not about getting the permission, because I'm a total free spirit," she says.

"Sean is great. He never says: 'It's a long time since you were at home for a Saturday, or to cook the Sunday dinner.' I'm the one who's out doing it - but he carries the burden. He financially supports me to do that, because I am a full-time volunteer. That's a huge gift. That's a lot of tolerance."

Adi's sister had very little tolerance for her when they were growing up in Clonmel, Co Tipperary. By her own admission, Adi was a pest who wanted to know where her big sister was going and why she couldn't go too. "I had a wonderful life in Clonmel, full of the usual things - chasing fellas, dancing, going to parties and singing songs," she remembers.

Adi's childhood dream was to be the next Margot Fonteyn. She even danced semi-professionally in Cork as a member of the Cork Ballet Company until she was 21.

Adi was six when she danced for the first time. "It was in a tutu. I used to love dressing up as a kid."

She hasn't lost that penchant for dressing up. When she attended the 2004 Academy Awards to pick up an Oscar for Chernobyl Heart, winner in the Best Short Documentary category, Roche looked ravishing in a red rig-out by her favourite Irish designer Mariad Whisker and a pair of problematic Manolo Blahniks she borrowed from a friend.

"I felt I had dropped in from another planet, because I am so not used to that world. Nori [her colleague] and I were the great unknowns. Nobody was interested in us. We were going down the famous red carpet and all the beautiful people were there and we decided that we had the only two faces in the whole of Hollywood that moved. Everybody was botoxed, lifted, ticked, stretched, pinned. We were the only two that looked real."

She recalls sitting outside the Vanity Fair party to rest her tootsies, tortured by the borrowed Manolos. To relieve the pain, she did a live interview for Gerry Ryan's RTE radio show. Her friend Ali Hewson, she says, "was listening to it in her car, and she said she had to pull over because she thought she'd have a crash she was laughing so much."

Adi seems very much the wide-eyed country girl from Clonmel when she talks of the excitement of staying in the hotel in which the movie Pretty Woman was made. But that is as far as her sense of wonderment at Hollywood went. "Because we weren't anybody we were able to be voyeurs. It's a world that they can definitely have. We went to all the after parties and saw all the stars, but it was a very lonely experience. There was an emptiness.

"I was sitting there thinking: 'We've won the Oscar but what does it mean?' At the end of the day it's a piece of metal. A grand piece of metal, but what does it mean to the people's lives who we invaded to make the film? What difference does it make to them? To me, it's always about that."

Adi is a product of both Cork and Tipperary. Her parents Sean and Chris were from Cork but lived in Clonmel. She clearly inherited her concept of social responsibility from them, as both were active in the St Vincent de Paul, Meals On Wheels - and Fianna Fail, though Adi herself, of course, ran unsuccessfully for the Presidency in 1997 with the backing of the Labour party.

She believes she also inherited her late father's work ethic. "My greatest failing - which is also the flip side, giving strength to everything - is that I'm a workaholic. I will work to the detriment of everything else - to the detriment of life, really. Actually, the recent death of my mother has given me an opportunity to rethink that. To slow down and say: 'Get a life.'"

And have you got a life?

"I'm actually starting to get a life. I'm actually singing with the girls. We're called The Bubbles," she says, referring to the collective of female singers specialising in a cappella and three-part harmonies. "I love a good time. If you saw me out on the town . . . "

So when was the last time she got physically ill from a night's drinking?

"God help us! That would be going back to another life."

ADI still finds the loss of her mother hard to bear. She lived with Adi and Sean for eight years. In fact, Adi was the primary carer for both her parents over almost a decade. (Her father, who died four years ago, had Alzheimer's.)

"Parting with my mother was very hard," she says. She was finishing the new Chernobyl Heart book when her mother went into a coma. "So the book has very mixed blessings for me. The last time I was with my brothers and my sister was at the funeral."

The day after the funeral Adi had to fly out to Ukraine with an RTE film crew. She couldn't cancel because it was something she had planned for six months. On that plane journey, Adi says she felt "a hole in my heart".

"I felt a whole mixture of emotions, but I also felt that my mother would have wanted me to go. She was one of my strongest advocates. She saw how lonely this job is as well. People just see the public persona."

And if there is a God, maybe he was testing you by showing you a fraction of the pain that the people in Chernobyl have gone through?

"Definitely. Through this work I have learned so much. It's so humbling. It is not about us being the benevolent ones or the great benefactors. The gift you get back you can't quantify, because it tells you about what it is to be a human, the privilege it is to be alive.

"There is something very cathartic as well. It's not about altruism for me. I say that to you in all honesty. It is as much about my own salvation as it is about doing good and I feel better for that."

It is not about Adi Roche sanctifying herself?

"Come here!" she laughs through the fog of a sudden deep culchie accent. "The broken wings, the broken halo, the fallen angel . . . absolutely, that is moi. Totally. And that's where I want to be. And there by the grace of God go all of us.

"The Belarussians are a kind people. If something happened in Sellafield, they'd have been the first to come to us. None of us can afford to be sanctimonious. None of us can afford to say: 'It's them and it's not us.'"

Adi is in the Merrion Hotel in Dublin to talk up Chernobyl Heart: 20 Years On, her new book that documents the physical, emotional and psychological pain that the nuclear disaster caused. (The book needs no talking up: with photos by former Sunday Independent photographer Julien Behal, it is equal parts harrowing and uplifting.)

She hopes that readers of the book will find it "breaks their hearts sometimes, but their hearts will soar with delight and pleasure when they read some stories." She also hopes the reader will cry the tears of those who have died, some of whose testimonials are told movingly here.

Adi wanted to give them a voice "regardless of whether they are still alive or not. They are environmental refugees, a status not recognised by the UN because no one ever anticipated an enviromental disaster such as this. They are a displaced people, hundreds and thousands of them.

"Sometimes they don't tell other people that they are Chernobyl survivors, because they are ashamed. Many of them have commited suicide, many have abandoned their own children - not because they don't love them, because they feel absolute despair and absolute paralysis."

Adi wanted to tell the human interest stories in the book because, she says, no statistics will ever "reflect the broken hearts and the pain and the agony. At the same time, we wanted to have a balance that wouldn't scare people off by having people so distraught that they can't read to the end."

She desperately wants readers to come to that beacon of hope at the end where they will hear about "thelikes of Ali and others who helped to make things happen, like the nurses, the doctors, the truckers."

Ali Hewson, a patron of Chernobyl Children's Project International, and Adi work well together. Ali is godchild to one of the Chernobyl children, Anna Gabriel. In 1993, Ali, according to Adi "agreed to break her own privacy" by going to Belarus to present Black Wind, White Land, a poignant documentary about life in post-disaster Chernobyl. Ever since, Ali and Adi have shared a devotion to revealing the truth of what they saw in Chernobyl.

"I think it touched a part very deep inside her. We were filming in a home for abandoned children and we ended up bringing home a child who was four or five months old at the time. She was about to be put in a mental asylum."

The child is now grown into a fine young woman and lives in West Cork. Ali, says Adi, is the consummate godmother, having attended all Anna's special occasions such as her confirmation, holy communion and birthdays.

As for Ali's immense contribution to the Chernobyl Children's Project, Adi says that people who are in the public eye "have a responsibility to use that celebrity for good".

"All I can say in relation to Ali is that - for me - she is the anchor person. She is far more reticent than I'd be. I am feet first. I want to save every single child, all four million. Ali would be of the philosophy that we do it one by one. That is far more realistic. In a sense, we have adopted that as our own mantra."

Is that why you work so well as a partnership, because you are such opposites?

"Ali says I talk a lot," says Adi. "When we drive in convoys, Ali does the driving and I do the talking. There is a serenity to Ali and her energy. Ali brings the reflective to things. When I want to dive feet-first into a situation, she wants to weigh up the pros and cons. Ali would be more pragmatic, more a strategist than I would be. There is a fine balance there."

Her mood turns darker as she talks about the nuclear radiation genie escaping out of the Chernobyl bottle. The cement tomb placed over the former power plant is far from effective. She talks with passion about the many workers who tunnelled under the reactor to install a cooling system "which saved Europe from being wiped out, because Chernobyl was about to have a second explosion."

Some 25,000 of the workers have died as a result and another 70,000 are dying at the moment. "I know many of these lads," she says. "I know one extraordinary helicopter pilot who was older than the others and had had his kids." He is now dying of strontium poisoning. "These guys sacrificed themselves."

In a way, so did Adi Roche. The Clonmel superwoman didn't die in Chernobyl, but she has practically given up her life for it. "I have," she agrees, "but I don't want that to sound self-sacrificing."

You don't have children, Adi. "I don't, because we had to make a decision in relation to the work. In a way, I would say that I have millions of kids. I honestly believe you don't have to have the umbilical cord connection to feel absolute, unconditional love for another human, whether it's a child, an infant or an adult."

"In the Seventies, we genuinely believed we were on the brink of nuclear annihilation. People really did wonder if they should have children or not. We made a decision based on what we knew and the ways things were going. But there are so many kids in the world that there's plenty of love to go around."

She adds that this means when when she visits orphanages or institutions, shecan completely give herself over to the children there. "Because I don't feel guilty that I've left kids at home. I would be up for neglect if I actually had kids. It would be one or the other."

She tells me that, once upon a time, the "conservative, strait-laced" Clonmel girl had a life that she thought would be about boy-meets-girl, gets engaged, married, has kids - the whole package.

She did meet the man, but what stopped that union flowering into the classic nuclear family (so to speak) was that Adi became involved in the anti-Nuclear Movement.

Her brother Donal was living in the US at the time, and his wife was having a baby. Adi arranged to fly over for the birth of the child as she was asked to be godmother.

The night before she flew out, there was newsflash on RTE about a nuclear accident on Three Mile Island in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania - near where Adi's brother lived.

Adi can recall turning to Sean at the time and asking him two questions. 'What's radiation?' and 'What's a nuclear reactor?' Sean said he didn't know, "but they want to build one of those down in Wexford" - a reference to Carnsore Point in Co Wexford.

"That was the beginning of it for me. I never had a life plan," she says, as she finishes her tea. "Because if I had known all those years ago that this was what I was going to end up doing, I'd have run in the opposite direction."

Thank God for the people of Chernobyl that she didn't.

'Chernobyl Heart: 20 Years On' by Adi Roche is published by New Island, €19.99

Barry Egan

U2Girl1978

Blue Crack Addict

Wow! She is really an amazing woman. I feel so bad for all those people that had and still have to go through this

This is heartbreaking.

Some 25,000 of the workers have died as a result and another 70,000 are dying at the moment. "I know many of these lads," she says. "I know one extraordinary helicopter pilot who was older than the others and had had his kids." He is now dying of strontium poisoning. "These guys sacrificed themselves."

This is heartbreaking.

kellyahern

Blue Crack Supplier

lauramullen

Blue Crack Distributor

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2002

- Messages

- 52,111

Thanks for those stills. Where are they from?

kellyahern

Blue Crack Supplier

lauramullen

Blue Crack Distributor

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2002

- Messages

- 52,111

Thanks. I just started to download.

u2granny

Blue Crack Addict

kellyahern said:

I think we keep downloading the same torrents.

kellyahern

Blue Crack Supplier

u2granny said:

I think we keep downloading the same torrents.

The Buenos Aires one is taking forfreakinever

u2granny

Blue Crack Addict

kellyahern said:

The Buenos Aires one is taking forfreakinever

I'm waiting for a few more seeds.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 869

- Locked

- Replies

- 1K

- Views

- 53K